If we want to end poverty, we could just ... end it.

Rather than relying on economic growth to eradicate poverty, Kerala is directly assisting those experiencing poverty with remarkable results.

Can economic growth end poverty?

The notion that economic growth is responsible for lifting most of the world's population out of poverty and therefore we need growth, is not supported by the data. After decades of relentlessly pursuing economic growth, half of the world's population live on less than US$6.85/day, a figure which accounts for purchasing power parity, ie. what US$6.85 will buy someone in the US. It's an incredibly low figure, especially when you consider that many Global North countries have a poverty line around the US$30/day mark: what we consider poverty for people in the Global South is far more extreme than what we consider poverty for people in the Global North.

For more issues with the notion that we need economic growth to solve poverty, this extract from The Divide: A Brief Guide to Inequality and its Solutions, by Jason Hickel is insightful:

Right now, the main strategy for eliminating poverty is to increase global GDP growth. The idea that the yields of growth will gradually trickle down to improve the lives of the world’s poorest people. But all the data we have shows quite clearly that GDP growth doesn’t really benefit the poor. While global GDP per capita has grown by 45 per cent since 1990, the number of people living on less than $5 a day has increased by more than 370 million. Why does growth not help reduce poverty? Because the yields of growth are very unevenly distributed. The poorest 60 per cent of humanity receive only 5 per cent of all new income generated by global growth. The other 95 per cent of the new income goes to the richest 40 per cent of people. And that’s under best-case-scenario conditions. Given this distribution ratio, Woodward [author of a study into growth and poverty] calculates that it will take more than 100 years to eradicate absolute poverty at $1.25 a day. At the more accurate level of $5 a day, eradicating poverty will take 207 years. This is the best we can expect from the business-as-usual trajectory of the development industry. And keep in mind that Woodward’s methodology is not able to capture the poorest 1 per cent of the world’s population, who will still remain in poverty even at the end of this period. That’s 90 million people who will remain in poverty for ever….

As if the epochal timelines here aren’t disappointing enough, it gets worse. To eradicate poverty at $5 a day, global GDP would have to increase to 175 times its present size. In other words, we need to extract, produce and consume 175 times more commodities than we presently do. It is worth pausing for a second to think about what this means. Even if such outlandish growth were possible, the consequences would be disastrous. We would quickly chew through our planet’s ecosystems, destroying the forests, the soils and, most importantly, the climate. As Woodward puts it: ‘There is simply no way this can be achieved without triggering truly catastrophic climate change – which, apart from anything else, would obliterate any potential gains from poverty reduction.’ It’s a farcical proposition – a cruel joke played at the expense of the poor. And, as if to add insult to injury, achieving this level of growth would mean driving global per capita income up to $1.3 million. In other words, the average income would have to be $1.3 million per year simply so that the poorest two-thirds of humanity could earn $5 per day. This gives us a sense of just how deeply inequality is baked into our economic system.

Source: The Divide: A Brief Guide to Inequality and its Solutions, Jason Hickel (pp.56-58)

It is clear that economic growth hasn’t been, and is not, our path to a world without poverty.

What could end poverty?

Instead of relying on economic growth to ‘lift all boats’, another option is to directly assist those living in poverty by providing them with the things they need so that they no longer experience poverty (novel, I know).

The Indian state of Kerala does this remarkably well. Extreme poverty has fallen dramatically over the last 50 years. In 1973-74 extreme poverty was 59.79 per cent (vs. the Indian average of 54.88 per cent), but by 2022, according to the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), Kerala’s extreme poverty levels had fallen to 0.55 per cent (vs the Indian average of 11.8 per cent). This index is based on 12 indicators “such as nutrition, years of schooling, child and adolescent mortality, maternal health, school attendance, cooking fuel, sanitation, drinking water, electricity, housing, assets and bank account”. Kerala scores well across all indicators, which is testament to the success of ‘The Kerala Model’ which focuses on human and social development without the need for economic growth.

What policies did Kerala implement to achieve such an impressive result? It was a comprehensive approach that included land reforms, universal and compulsory school education, decentralised democracy, healthcare initiatives and extensive social security schemes that provided a safety net for approximately 6.5 million people. Launched in May 1998 by the State Poverty Eradication Mission (SPEM) of the Government of Kerala, ‘Kudumbashree’, has also been instrumental in lifting vulnerable populations out of extreme poverty.

Earlier this year, Kerala’s Chief Minister announced an ambitious plan for extreme poverty to be eradicated in the state by November 1, 2025. It will be the first state in India to do so. What a contrast that is to our global plan to eradicate extreme poverty, which will take 100 years or longer and destroy the ability of the planet to sustain life in the process.

What is Kudumbashree and how does it work?

While many of Kerala’s anti-poverty policies I’ve outlined above are fairly intuitive and straightforward, Kudumbashree may be a new concept for many people, and so I am going to explore the details of the program further. Literally meaning ‘prosperity of the family’ in Malayalam, Kudumbashree is both a poverty reduction and a women’s empowerment program. Kudumbashree’s initial aims were to emancipate low income women from the “four walls” of their homes and engage them in social, economic and political life by fostering self-supporting women’s groups.

Membership into the program is open to adult women, but restricted to one woman per household. The program has nearly 4.5 million members reaching nearly 60 per cent of Kerala’s households, making it one of the largest women’s networks globally. Kerala’s Kudumbashree has been described as one of the “greatest gender justice and poverty reduction programs in the world”, with its contributions being “unmatchable in reducing poverty significantly.”

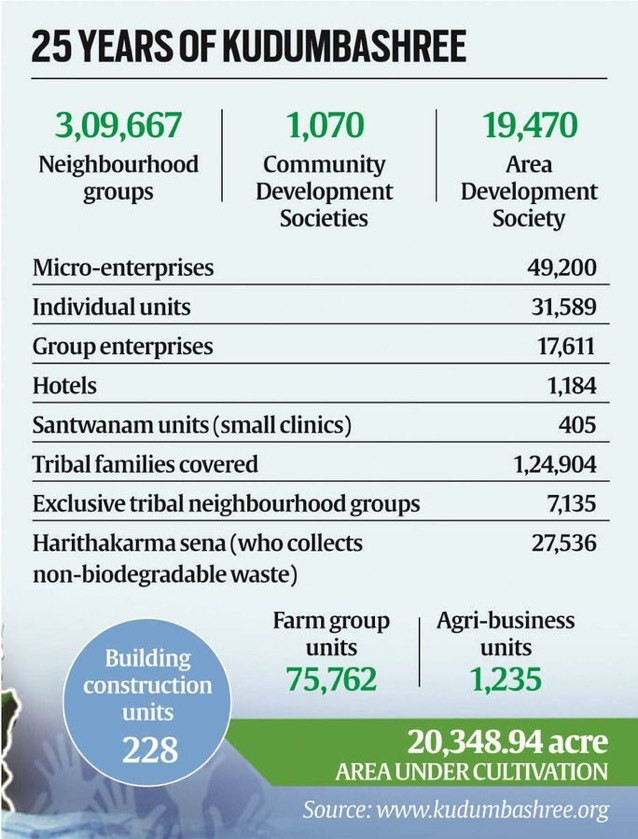

Kudumbashree empowers women by providing them with employment opportunities, access to decision making bodies, encouraging thrift and internal lending, and facilitating the start-up of micro enterprises. It follows a three-tier structure of Neighbourhood Groups (NHGs), Area Development Societies (ADS) at the ward level, and Community Development Societies (CDS) at the local government level.

NGHs are the heart and soul of Kudumbashree and consist of ten to twenty women per group. They meet weekly at an agreed time and date and the meeting is to be held at the houses of members on rotation. In terms of the collection and dissemination of the thrift and internal lending that make micro-enterprises possible, there is a detailed and democratic process for NGHs to follow:

In the weekly meetings, members deposit the pre-fixed thrift amount with the secretary and get the corresponding figure entered in the passbook and signed. NHG can issue small loans from the group’s savings to its members as per requirement. All decisions are to be taken by consensus or through majority support. All loans are subject to decision of the NHG.

The weekly thrift amount for members is fixed as equal to the weekly savings that the poorest member of the NHG can afford to make. Even though this is the general rule, NHGs may decide to allow reasonable levels of variation in the weekly thrift amount among members. Members who do not have [a] source for savings at all are exempted from weekly savings. However, the exemption is not applicable for [the] membership fee.

In the case of those who have been exempted from weekly savings, their exemption does not prevent them from availing subsidies, financial assistance, and other support provided by the government and other agencies.

Once an NHG is formed, it works for three months with regular meetings and savings by members before it starts internal lending. Loans are approved by consensus or majority decision by the group after examining the demands by members put forward in weekly meetings. It is the prerogative of the group to decide on [the] priority. NHG charges interest on loans at rates decided by the group.

Source: The Kudumbashree Story

There are over 300,000 NHGs, with more than 49,000 micro-enterprises under the program. Kudumbashree women participate in a variety of sectors, including farming, childcare, managing non-biodegradable wastes, running ‘Janakeeya Hotels’ (providing food to the poor), kiosks, digital marketing, health clubs, home stays, occupational trainings, palliative care, community counselling and more.

Beyond the impressive results in poverty reduction, the program has been incredibly successful in raising women’s presence in legislative bodies, with women now constituting “54% of Kerala’s 21,900 local body members; about 70% of these women are from Kudumbashree.”

What makes Kudumbashree special?

Now in its 25th year, the Kudumbashree program has played a significant role in strengthening community bonds and creating a sense of solidarity. It provides women with independence and autonomy and creates a link between the government and the ‘common’ people: “‘We work with governments, not for governments’, is a motto of Kudumbashree women. Part of the reason for its success is that it has a diverse membership, which cuts across religious and communal boundaries.

Group farming, or ‘sangha krishis’ has been a particularly successful element of Kudumbashree. In a country where thousands of people quit farming everyday, Kudumbashree has brought around 350,000 women into agriculture, increasing their food and livelihood security. Thousands of acres that would otherwise be unused land has now been brought under cultivation for rice, vegetables and fruits. The sangha krishis prioritise the wellbeing of the collective over profit, aligned with Kerala’s strong social justice and cooperative ethic:

There are 70,000 sangha krishis, each with five members on average. Every group works on leased land, usually less than two and a half acres. Sometimes, just a single acre. Most practice organic or low-input sustainable agriculture. In a country where farming is in a shambles, these women have run their tiny leased-land farms on profit and on a principle of ‘food justice’ – surplus produce can be sold on the market only after all the families of the group farm have satisfied their own needs.

Source: ‘Kerala’s Women Farmers Rise Above the Flood’, The Wire

What does the future hold for Kudumbashree?

The program is seeking to increase the number of households it reaches from nearly 60 per cent to 75 per cent of Kerala’s households, and move the focus away from poverty reduction to businesses and community empowerment. It is also looking to target younger and highly educated women, providing them with an entrepreneurship program to create micro-enterprises (5,000 have already been created). In addition, women from the program are helping to replicate the program in other Indian states, and the governments of South Africa and Ethiopia have also expressed an interest in learning more about the program.

What can we learn from Kudumbashree and The Kerala Model in general?

The Kerala Model, including Kudumbashree, shows us that further economic growth is not required to lift people out of poverty. Rather, we should be directly providing those experiencing poverty with the things they require to meet their basic needs, be it education, housing, employment, healthcare, money or self-help or community-based programs. Perhaps these self-help/community-based programs are similar to Kudumbashree, or perhaps they are more like Mondragon (Spain), Cooperation Jackson (US), Cooperation Richmond (US), or The Preston Model (UK), all of which I will explore in more detail in future newsletters.

This is aligned with step one of implementing degrowth: to provide people with the things they need to live a prosperous life, including universal basic services (healthcare, education, transport, water, electricity etc), a job guarantee and a reduced working week. This would enable us to reduce material and energy throughput while improving people’s sense of wellbeing.

Which begs the question, why do we continue to pursue economic growth? It just doesn’t make sense on any level, beyond the fact that the very wealthy reap the rewards of economic growth and don’t want things to change. It is those very same people who have control of our politics, media and education systems so, through a process of ‘cultural hegemony’, we’ve unwittingly adopted an economic system that doesn’t serve us, our environment, or future generations, but does serve those who benefit most.

Protecting the Future exists because of my paid supporters who see the importance of this work. If this project is of value to you, consider becoming a paid subscriber today.

If this piece resonates with you, you may like some of my other articles:

The Kerala Model

Kerala is doing A LOT right I recently watched this 1 minute and 41 seconds long video on the Indian state of Kerala by @karishmaclimategirl on Tik Tok, where Karishma describes Kerala as “representing the success of degrowth”. I was keen to know more and what I learnt did not disappoint. Here is the video:

Buen Vivir

Image: Painting depicting buen vivir as the renewal of Kichwa society, by Juan César Umajinga of Quilotoa, from the personal collection of Joe Quick I am very interested in the ways of life that already exist around the world that are aligned with the concept of degrowth. These ways of living show us that we are not in the