Imagination and Possibility: Part 3

We can - and should - imagine a better world, and it helps if we know what is possible.

Photo by ameenfahmy on Unsplash

Possibility is everywhere

In this three-part series on the power of imagination and possibility, I explore degrowth-aligned policies or actions that have been implemented around the world. They serve as proof that such outcomes are attainable, provide a potential blueprint for how similar policies could be achieved and ignite our imaginations on what our futures could hold.

This piece is part three in the series. In part one I explore nationwide mining bans, car-free towns, deprivatisation of utilities, nationwide meat bans and local currencies. In part two I delve into social housing, job guarantees, the 4-day work week, maximum incomes and socialist societies. In this, part three, I look into cooperatives, bottled water bans, reversing deforestation, ecological urban design and the inalienable rights of nature. My hope is that, through seeing these alternatives to the current dominant narrative in action, we realise that degrowth-aligned policies are actually much more widespread than we realise.

1. Cooperatives, not corporations

For a long time we have used ‘growth’ and the idea that we will all benefit from a bigger pie, to avoid addressing inequality head-on. This will become unavoidable in a degrown, smaller economy, and the institutions that serve to funnel wealth to a small percentage of the population whilst suppressing or reducing the wages of the majority of the population will become obsolete.

Cooperatives are an organisational structure whereby members or workers are the owners. This means the owners are involved in the day-to-day running of the organisation and the ecosystem in which it operates. This is unlike public corporations whereby the owners (that is, shareholders) may not not even realise they hold shares in the company because their funds are managed by an intermediary (think pension funds). In this instance corporations are tasked with generating the greatest return for shareholders, year on year on year. This is the engine room behind the growth economy.

There is no such growth mandate on cooperatives, who can therefore have much broader social and ecological goals. One of the largest cooperatives in the world is Spain’s Mondragon. Launched in 1956, Mondragon consists of 95 seperate worker-owned entities and employs over 85,000 people. At Mondragon there is a focus on grassroots management and democratic decision making, with each worker’s vote being valued the same, regardless of the employee’s position within the organisation. Employees share in the success of the organisation, and also in the hard times, shifting resources between entities to avoid job loss. For example, during the COIVD-19 stay-at-home orders many entities democratically decided to reduce workers hours and/or salaries until the markets improved.

Mondragon is not perfect. In many cases its cooperative structure doesn’t extend to its overseas operations. It also functions within a growth-based economy and needs to remain competitive for its survival, often putting pressure on the organisations to simultaneously grow and reduce costs. This episode of the Upstream podcast looks in-depth at Mondragon and the challenges it faces. Other examples of cooperatives being created to build solidarity, resilience, equality and justice include Cooperation Richmond and Cooperation Jackson. In both of these instances cooperatives are being created to build community and keep economic flows within the respective town, improving the living standards for residents in the process. The “degrowth in practise” Indian state of Kerala, is also an excellent example of utilising cooperative structures to put people and the planet at the heart of decision making. Kerala is 3% of India’s total population, but represents 17% of its cooperative memberships.

Cooperatives are not the entire solution, and many do still seek growth in sales and profit. There are other features a cooperative should adopt as a part of a degrowth/post-growth compatible organisation, but they are potentially a big piece of the puzzle.

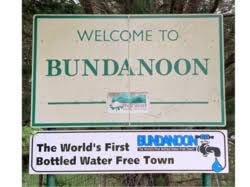

2. Bottled water bans

Image: the sign on a door of a local shop in Bundanoon, source Wikipedia.

In 2009, under the grassroots campaign ‘Bundanoon on Tap’ the small town of Bundanoon in Australia’s New South Wales Southern Highlands became the world’s first single-use bottled water free town. Bundanoon has installed water fountains in pedestrian areas and cafés offer tap water instead of selling bottled water.

This might seem like a very small scale example, but it’s a wonderful illustration of degrowth in action. Bundanoon’s citizens democratically decided that they didn’t want to support the bottled water industry, and so they shut it down. There’s no reason - beyond the erosion of democracies by big business and the ‘elite of the elite’ - that we can’t do this in more places and at a larger scale.

Image sourced from the Bundanoon on Tap website.

Sadly, the outskirts of the town is the site of 50 million litres of spring water being extracted each year for bottled water companies. It was through the process of citizens objecting to the depletion of their aquifers - that ultimately they were powerless to stop due to the permission being granted over a decade earlier - that they learnt about the harm caused by bottled water and came together to remove its sale from their town.

3. Halting and reversing deforestation

Costa Rica is the only country in the world that has managed to halt, and then reverse, deforestation. Since the implementation of forest protection policy in 1986 forest cover has more than doubled, increasing from 24.4% to 57% today, a figure the government says is near maximum (some parts were never forested and others are now cities or productive farms). This was possible because the government made it more financially viable for landholders to reforest the land than to use it for animal agriculture. The plan was incredibly successful, with 97% of participants protecting or restoring the trees on their land.

Image: La Fortuna Waterfall, Costa Rica. Photo by Etienne Delorieux on Unsplash

As a result of Costa Rica actually valuing their forests, its wildlife is now flourishing, and the country is a top destination for eco-tourists. Eco-tourism is now the second largest source of revenue for the country. Costa Rica is also punching above its weight on the world stage, inspiring several programs to protect and restore degraded land across the world.

4. Ecological urban design

I sometime come across tweets like this, and they are a pretty stark reminder of the huge amount of work that is yet to be done:

Source: Prof. Steve Austin on X

Have you ever driven through a brand new housing estate and wondered “where are these people supposed to shop? Where are the cafes and corner stores and how do they create a sense of community?” Same. Although I suspect the US and Australia are particularly guilty of creating a monoculture of over-sized suburban houses, given both countries have some of the largest homes on the planet.

Tokyo is a refreshing and inspiring example of an alternative to the single-use zoning we see in many countries. Joe McReynolds, co-author of Emergent Tokyo: Designing the Spontaneous City, explains:

This is going to sound wild to anyone who lives in the US, but for any two-story rowhouse in Tokyo, the owner can by right operate a bar, a restaurant, a boutique, a small workshop on the ground floor — even in the most residential zoned sections of the city. That means you have an incredible supply of potential microspaces. Any elderly homeowner could decide to rent out the bottom floor of their place to some young kid who wants to start a coffee shop, for example. When you look at what we call yokocho alleyways — charming, dingy alleyways that grew out of the black markets post-World War II, which are some of the the most iconic and beloved sections of the city now — it’s all of these tiny little bars and restaurants just crammed into every available space.

Source: ‘Why Neighborhoods and Small Businesses Thrive in Tokyo’, Bloomberg

The path out of these sprawling suburban wastelands towards well connected (via mass transit), vibrant communities and 15-minute cities is going to need an approach that leads to multi-use and multi-family zoning. The changes will need to be:

regulatory: making it viable for small businesses to operate in smaller suburban spaces;

political: removing the structural car dependency that has been engineered by lobby groups over decades;

cultural: for many people these suburban homes represent ‘success’ but this definition of success multiplied by large numbers of people is isn’t feasible within our planetary boundaries

financial: ensuring that homeowners aren’t reliant on the value of their property to fund their retirement, and that others can’t profit from anti-ecological town planning.

The pay-offs would be tremendous, not just for the planet, but for residents too.

Image: Beautiful multi-use suburbs, source: @thepeterlaing on X

5. The inalienable rights of nature

In September 2008, Ecuador became the first country in the world to recognize the rights of nature in its constitution. Bolivia quickly followed suit, in 2010 and 2012 it also passed national legislation which recognised the rights of nature. These rights include:

… the right to life and to exist; the right to continue vital cycles and processes free from human alteration; the right to pure water and clean air; the right to balance; the right not to be polluted; and the right to not have cellular structure modified or genetically altered.

Controversially, it will also enshrine the right of nature "to not be affected by mega-infrastructure and development projects that affect the balance of ecosystems and the local inhabitant communities"

Source: ‘Bolivia enshrines natural world's rights with equal status for Mother Earth’, The Guardian.

These pieces of legislation came about through powerful indigenous and grassroots social groups and have important ramifications. In 2021 Educador’s highest court ruled that a proposed copper and gold mine in the protected ‘cloud forest’ of Los Cedros was unconstitutional and violated the rights of nature. Previously issued mining concessions and environmental and water permits had to be cancelled. The many endangered species within the forest, including endangered frogs, the spectacled bears, the spider monkey, many types of birds and plants “won an unprecedented battle”. Just imagine the impact of such legislation across the world.

There’s so much more I could add

In researching these examples of degrowth aligned policies that have been implemented across the world, I realise now I could probably just have a weekly newsletter on this topic, there are so many wonderful examples. Alas, I won’t be doing that. But I will briefly list some other inspiring policies we’ve seen across the world, with links to more information for those who want to delve further:

The implementation of carbon taxes in various countries;

Strong labour unions (eg in Bolivia and Kerala) which enable governments to act in the best interests of people and the planet rather than profit and growth;

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons provides a historical precedent for a Fossil Fuels Non-Proliferation Treaty;

France’s ban on short-haul flights;

Wales’ freeze on new road-building projects, with the money saved invested in improving current road infrastructure and creating public and active transport routes;

Cities encouraging people out of their cars by providing free public transport;

The Costa Rican (“la pura vida”) and Uruguayan cultures of living simply;

Ad-free cities, because “[A]dvertising breaks your spirit, confuses you about what you really need and distracts you from real problems, like the climate emergency”;

The Greek Islands of Gavdos and Ikaria. A Ikarian audience member in a presentation on degrowth commented: “we’ve lived this way long before you invented degrowth!”;

Community solar schemes taking the energy transition into their own hands;

Radical democracies such as Kerala, and the surprisingly life-aligned policy recommendations from citizens assemblies.

I’m sure this list is incomplete and there’s more inspiring examples of degrowth aligned policies. Please do let me know in the comments what I’ve missed.

Democracy is not a spectator sport

The examples I’ve shared in this article, and the previous two parts, show that when people are invested in the decision making process good things can happen. It is possible to have policies that have people and planet at the heart of them, and not profit and growth, but only if citizens are pushing for them.

So, remember: democracy isn’t a spectator sport. We can’t sit this one out.

Next Tuesday: This three part series on Imagination and Possibility feels a little disingenuous if I don’t also cover of the many times that a socialist government with ecological principles has been elected into office democratically, only to be undermined by Western interests. While this topic feels heavy, if we are going to do what is required we need a full understanding of the situation. Look out for that next week.

Protecting the Future exists because of a small number of paid supporters. If this project is of value to you, consider becoming a paid subscriber today.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also like the first two articles in the series:

Imagination and Possibility: Part 1

Photo by Lucas Chizzali on Unsplash We can achieve incredible things Every now and then I stumble across something that I think is astounding. A huge win against the odds that stands out like a beacon of possibility in a sea of business-as-usual extraction and domination. I can’t help but let my imagination run away with what might be possible if such dra…

Imagination and Possibility: Part 2

Photo by Jill Heyer on Unsplash It always seems impossible … In this three-part series on the power of imagination and possibility, I explore degrowth-aligned policies that have been implemented around the world. They serve as proof that such outcomes are attainable, provide a potential blueprint for how similar policies could be achieved and ignite our i…